If “class” sounds boring to you, that’s because few involve hitting a steel plate at one mile with Gunwerks. A mile…1,760 yards. But with expert instruction on reading and understanding the wind, advanced ballistics, calculating for such things as spin drift and Coriolis effect, and shooting techniques, Gunwerks’ L201 Advanced Long Range Shooting course will get you there. But first you have to get to the class . . .

Gunwerks runs L2 classes in Wyoming, Texas, Michigan, and other locations. They’ve also done events that combine L1 and L2 classes with a hunt at locations such as the NRA Whittington Center in New Mexico, and they run hunts around the globe.

As a freshly-minted Texas resident (back when I attended this class), I packed up the rig previously known as the “woods truck” and headed about three hours north to Warren Ranch. With the 75- and 80-mph TX speed limits (there’s even a stretch of road just South of Austin with an 85-mph posted limit) one can get pretty far in a few hours, even going through such places as Mills County, the “Meat Goat Capital of America.” Not ba-a-a-a-d. Hard to bleat, really.

The seven thousand acre Warren Ranch offers long distance shooters a covered rifle range with steel targets from 350 to 1,440 yards, including animal silhouettes. Plus a slab of steel in the other direction that’s a full mile away. There are classroom facilities, a fully-outfitted lodge, sports facilities, a fishing lake, a par-three golf course, horseback riding, guided hunts . . . you’d have to be boring to be bored here.

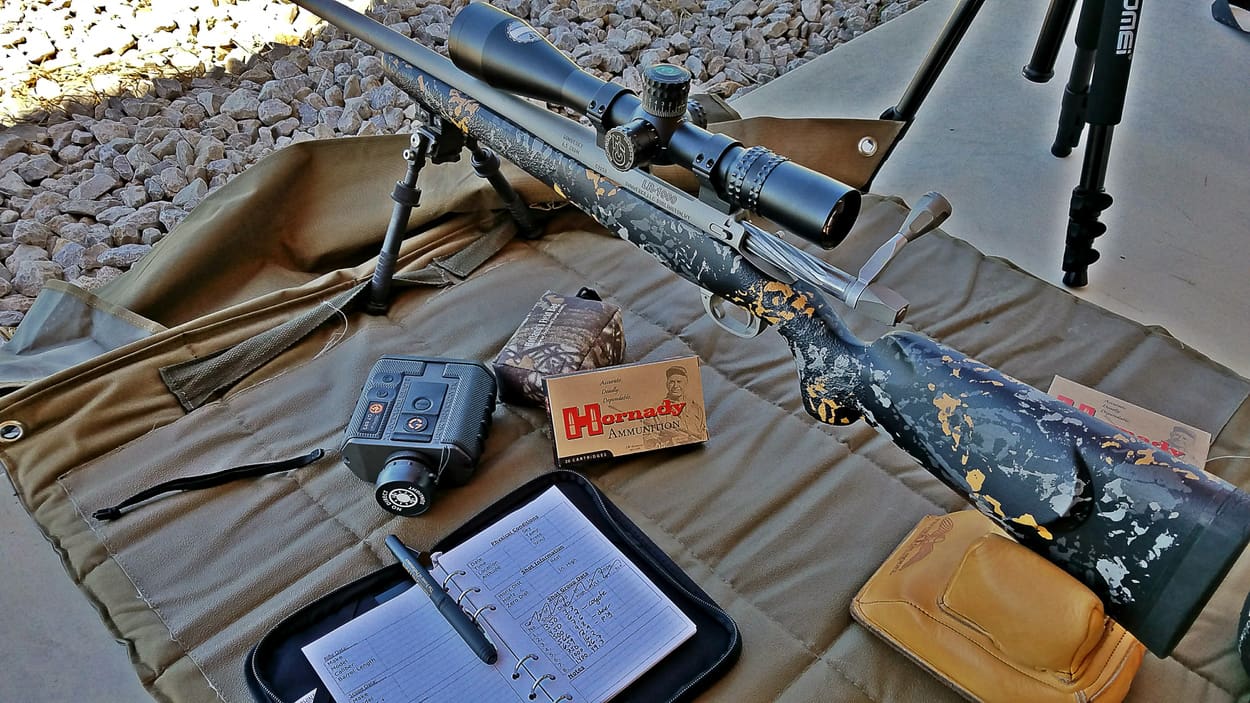

Gunwerks’ customers are busy professionals; the class I attended was comprised of doctors, lawyers, and business owners/executives. Gunwerks fills a niche by selling customers like this a complete system, not just a rifle. A combination of equipment and ammunition that delivers on Gunwerks’ “1,000 yards out of the box” slogan, including:

– A custom bolt-action rifle in your choice of caliber, action, barrel, stock, finish, brake, magazine style, etc.

– A mounted and zeroed (at 200 yards, typically) optic, usually with a custom-engraved ballistic turret

– Bipod/rest setup

– Gunwerks match ammunition

– Gunwerks G7 BR2 Ballistic Rangefinder

If that sounds more like a package than a “system,” it’s the human element that seals the deal. Gunwerks verifies the ballistics of each individual rifle with the owner’s preferred load and adjusts the range finder’s ballistics calculator and the custom elevation turret accordingly.

When the owner pulls their new Gunwerks rifle out of the box, ranges a target at 934 yards and the rangefinder tells them to dial 24.2 MOA/96.8 clicks (or gives them an air density- and shooting angle-corrected distance to dial in yards, should they have a ballistic-matched turret), it’s on. Whether it’s a steel deer or a real deer downrange, with that load in that rifle with that optic, the owner is dialed in.

Or at least the gun is . . .

To get the owners on board, there’s Gunwerks Long Range University, Levels 1, 2, and 3.

– L1 is primarily about gaining intimate knowledge about the firearm and components, using and maintaining the equipment, and solidifying shooting fundamentals. Gunwerks provides the guns and ammo.

– L2 gets into long range ballistics, internal ballistics, reading and understanding the wind, properly placing shots on animals, ranging with the reticle, configuring the G7 rangefinder, and shooting from various field positions. Again, Gunwerks provides the guns and ammo. This is the class I joined.

– L3 leaves the classroom, ups the difficulty, and provides instruction in the field with your own equipment.

The wind. Oh, the wind. Calling it is tough. If you’re shooting long-range it’s absolutely critical. Shooting the slippery 6.5 Creedmoor at 1,440 yards, I found myself holding 10 minutes — about 12.5 feet — left of the target to account for a ~9 mph 9:00 wind.

With modern rangefinders, using consistent rifles and ammo, missing up/down ain’t no thang. But, again, the wind. Which is why James Eagleman, Gunwerks’ Director of Shooting Instructions and actual long-range Operator, spent the majority of the first day’s three hours of class time on doping the wind.

James taught us to see mirage. Where to focus your spotting scope or binoculars, where not to, what kinds of backgrounds are best for spotting mirage. Then he taught us what it all means. Waves, angles, diamonds to read speed and direction. It’s a system he developed, and the one now taught to Uncle Sam’s best snipers.

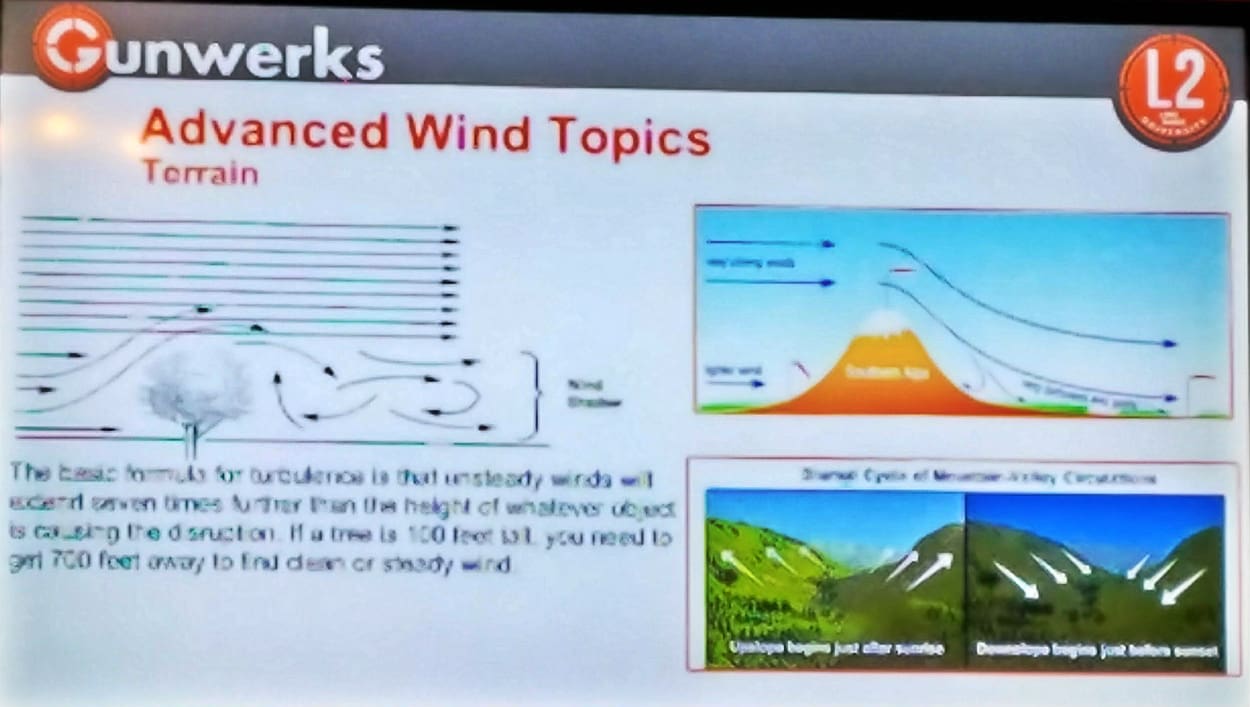

Of course, determining wind direction and speed is just one part of a mess of potential variables. We learned how wind behaves around all sorts of terrain and in all sorts of scenarios. We were reminded that it doesn’t necessarily matter what the wind is doing where the shooter is or where the target is if that’s different from where the bullet will spend most of its flight.

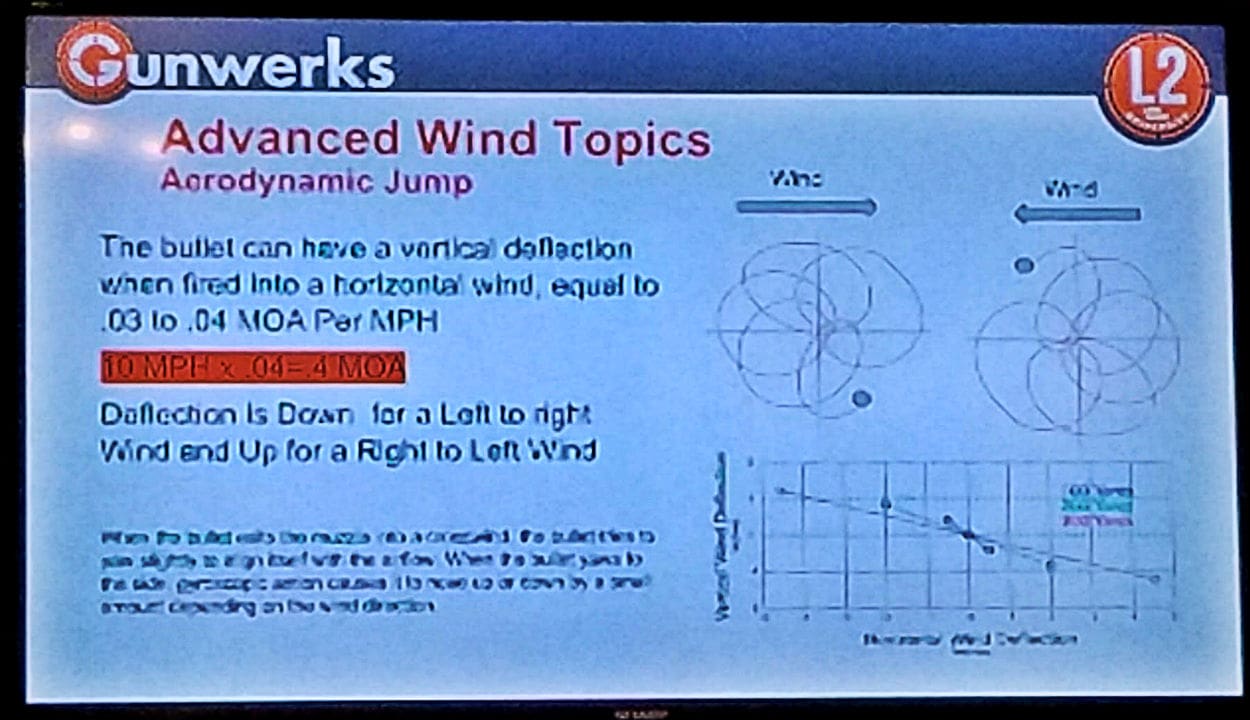

We learned that a crosswind can affect elevation adjustment, too. In the example above, a 10 MPH wind can move the bullet up or down by 0.4 MOA. At 1,000 yards that’s nearly 4.2 inches.

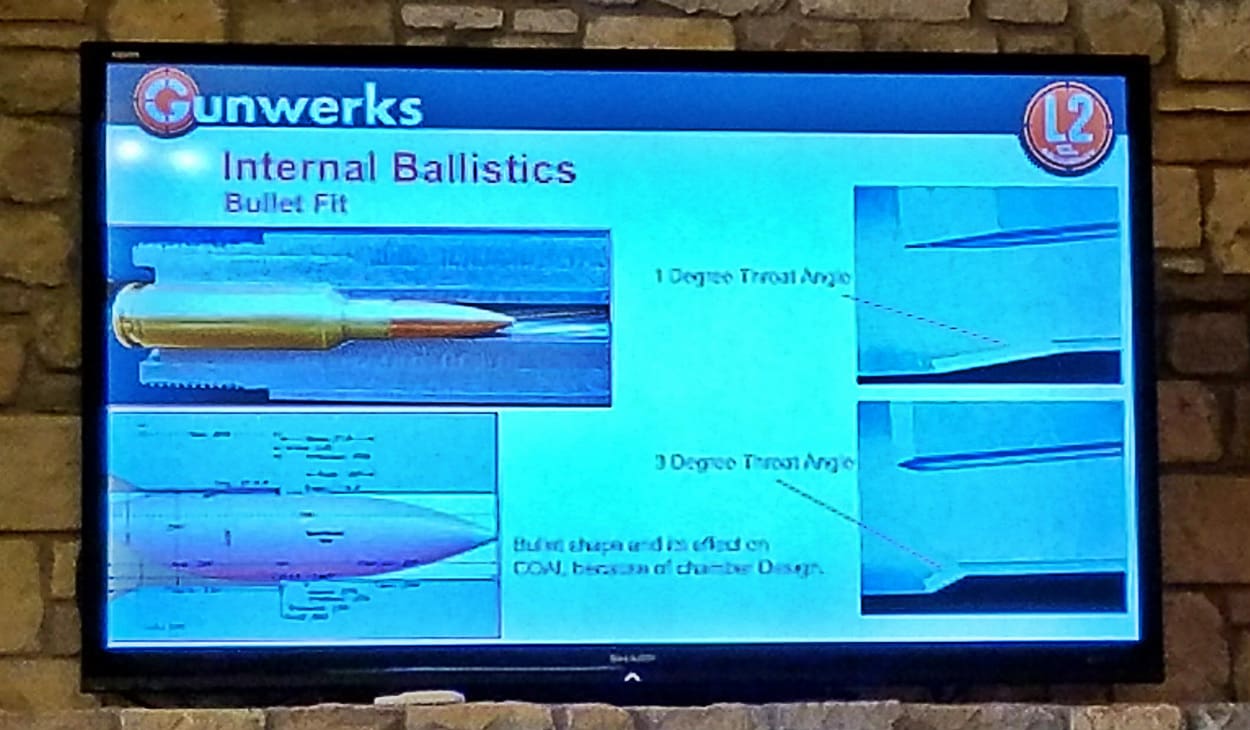

We learned many aspects of internal ballistics, from bullet ogive shape to throat angle to interesting things about barrel harmonics, load development, pressure signs, barrel length, powder choice, and more.

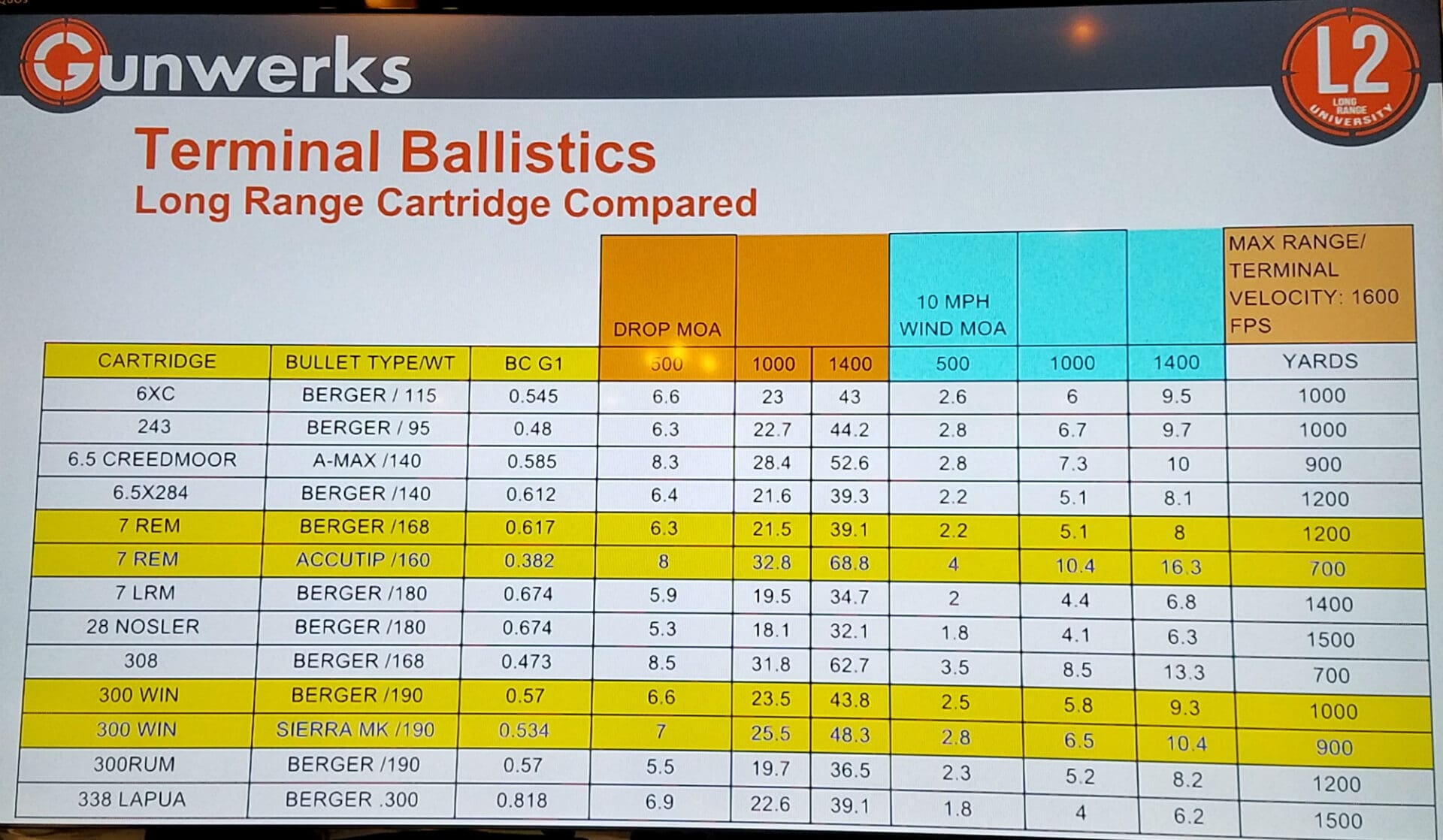

We learned about external ballistics. This included discussions of ballistic coefficient and the effect that range and wind have on different calibers. It also included various aspects of terminal ballistics, including bullet construction and its effects on terminal behavior (expansion, wound cavity, penetration, etc), maintaining sufficient velocity for the bullet to behave properly, and shot placement on various types of game.

Day 2’s shot placement discussion examined the fascinating distinction between North American game (bear and bison excepted) and African game. James discussed skeletal structure and wound cavities as they relate to both projectile choice and shot placement.

He also touched on knowing your limits for making an ethical, clean kill shot on an animal, and how to adjust location for wind, terrain, distance, and other variables to improve your odds.

James then demonstrated a range of shooting positions that can be employed in the field: prone, pack-supported seated, kneeling, standing, using objects like trees and fences, and more. He demonstrated the positions with and without tools like bipods, tripods, shooting sticks, and slings.

Seen above, James has wrapped his sling around the front leg of the tripod — sling or not, correct orientation of the legs (human and tripod) is also important — with the muzzle pointing a bit downward. He then creates tension by taking a shooting position and weighting down on the stock as the sights come up on target. Elbow on knee to seal the deal, this looked pretty darn solid.

https://youtu.be/Bm3A8cy7QzQ

We took all of this new knowledge straight to the range. On Day 1, we spent about half the time spotting for a partner, working on calling the wind based on mirage. James pointed us in different directions at different ranges and walked us through spotting scope focus and how to see what he sees and what it means. Heat mirage can be seen in the video above, primarily in front of dark objects in the background, though the focus is incorrect for reading the wind.

After engaging targets at all available distances from the prone, we were encouraged to shoot from various field positions with the help of the aforementioned tripods, bags, and shooting sticks.

I found kneeling and leaning into a wide-based tripod to be very effective. I put my first shot at 1,440 yards on the bullseye and the second one about 7-8″ away. A couple more went into the 10″ circle around the bull. In general hits were walking left-right across the steel plate due to a variable 8 to 11-ish mph full-value wind.

https://youtu.be/_yu34kXyNiI

The video above shows hits on targets from 350 yards to 1 mile. On some of them, the trace of the bullet disturbing the air on its way downrange is quite visible. How about stacking three shots on top of each other on the bullseye at 667 yards? An exceedingly well-sorted bolt gun shooting 6.5 Creedmoor, a nice optic, and a TBAC can is a solid setup indeed.

Seen above are a few hits on 750-yard steel. Interesting note: the target on the right was shot while standing next to the rested rifle, touching it only with thumb and trigger finger. James did it first — demonstrating a stable rest and not screwing up alignment with the trigger pull — hitting a scant few inches right of the bullseye. Benefiting from his take on the wind hold, my shot cut the distance to the bull in half.

https://youtu.be/qSD_4hrz3OM

For the record, this impressive accuracy was all with factory ammo rather than Gunwerks’ custom loads. We were shooting Hornady 140 grain ELD Match in 6.5 Creedmoor.

https://youtu.be/4k1-zvVBlrc

At the one-mile target, my classmates broke out their personal Gunwerks rifles. The video above is with a Gunwerks 28 Nosler. There was also a sweet .338 Lapua Mag in attendance and a couple 7LRM rifles (Gunwerks’ own 7mm Long Range Magnum caliber).

For me, the Gunwerks’ course was all about the wind: learning to better identify its strength, direction, and effect to shoot more accurately and be a better spotter. My phone app takes care of density altitude, temperature, bullet drop, spin drift, and Coriolis effect (see HERE). But it can’t tell me what the wind is doing on the way to the target.

I’d like to see the L201 class double down on the level of wind-calling instruction by using video examples that clearly demonstrate mirage in various conditions against an ideal background. With the generally light-colored background at the ranch, mirage was tricky to see. Students had a difficult time recognizing all of what James was describing, and we had good weather for it.

On the equipment side, the rifles and rangefinders are top of their class. The four rifles I shot were butter smooth, crisp, precise, and accurate. We’ll be borrowing one soon to follow up with a full-on gun review.

Gunwerks Long Range University L201: Advanced Long Range Shooting

Ratings (out of five stars):

Overall * * * *

I’m a better shooter because of this class — better behind the gun, better behind the spotting scope, better when hunting. I know more about the behavior of the wind and how it affects bullet trajectory. I know more about internal ballistics such as throat angle, barrel harmonics, bullet seating depth, and more.

L201 just misses the five-star mark due to missing the chance to drive home the students’ understanding of reading wind via heat mirage with canned, real visuals. It was too difficult to see in these field conditions for most students, and it was one of the most important and valuable portions of the two-day class. James asserted that “once you see it, it clicks,” and I don’t doubt that whatsoever. But let’s make sure students see it.

I’d love to take that class.

$2,500 is a bit steep for my budget… 🙂

And this illustrates why I have not pursued “long range” shooting: it is cost-prohibitive to do it right.

An outstanding “long range” rifle has to cost at least $1k.

An outstanding “long range” scope and mounts has to cost at least $1k.

An outstanding “long range” rangefinder has to cost at least $1k.

And I can easily picture a good supply of precision ammunition easily costing $1k.

That is a total of $4,000 in equipment/hardware alone.

Now we have to include the cost of the class which I imagine is upwards of $2k.

Finally, many of us will have significant travel costs which could easily approach $1k.

And I did not even bother to mention lost productivity or vacation time cost nor the ongoing costs of continuing to maintain or improve on your skills.

Add it all up and it looks to me like getting into the “long range” shooting games has an entry fee of about $7,000. Sadly, I cannot justify spending that kind of money at this time — or for the foreseeable future.

Most people don’t have access to a range that long anyway. How about a 22 magnum bolt action with a scope and pretending that 200 yards is 1,500 yards? Still fun.

That is actually very good practice.

I’ve been prairie dog shooting and ground squirrel shooting.

Scoring a first round hit at 200 yards is very challenging.

I really want to try this with a 22-250 or 6.5 CM. First I need to load up about 500 rounds for a good weekend.

Having a place to shoot long range is always an issue.

Here it’s hard to get past 400 yards unless it way out in the farm country. If I ever won the lottery I would build a facility servicing NE Georgia, TN, SC, NC. In Alabama there is a 1000 yard range I am visiting in the spring of 2021..unless “the covid” or some other 2020 nonsense.

Wrong on all account. Assuming we consider long range having a system capable of shooting out to 1000 yards, it can all be accomplished for about $1000. A cheap Ruger American or Savage in 6.5 can be (or could be,) had for about $500, an SWFA SS 10×42 can be had for $300, $200 used, some decent rings/mounts can be had for $50, and a Harris or Magpul bipod can be had for less than $100. You don’t need a rangefinder, since you can do simple mathematical calculations using your scope’s reticle to figure out distance to target. Nor do you REALLY need a class. Pick up Ryan Cleckner’s The Long Range Shooting Handbook and teach yourself everything you need to know to get started making hits at long range.

I’m not saying you’ll be competitive in the PRS circuit, but you’ll definitely be able to have some fun at longer ranges.

This guy was talking about shooting out to a mile, though. The cost equation changes a lot when you start exceeding the capabilities of the cheaper calibers like 308 and 6.5CM and have to use some more expensive stuff.

I’d also point out that the class described here is teaching you how to get consistent first round hits, not plink and tweak your way on to a big piece of steel. While I agree that plinking at 1000yds is a great way to spend a day, it’s not REALLY teaching you the kind of high performance shooting that this class is doing (supposedly).

Chainsaw,

You pretty much read my mind and said what I would have said in response.

It is one thing to “goof around” and try to hit steel gongs at 1,000 yards. It is an entirely different matter to hit a target the size of the vital area of a game animal (or human) out to 1,700 yards on the first shot, and without knowing the exact distance before pulling the trigger.

And the class referenced in this article teaches how to account for variables such as atmospheric pressure, air temperature, shot bearing (azimuth) and latitude, bullet spin-drift, and more that will cause you to miss that first shot at long ranges.

Extreme performance costs money, and I think we do a disservice to the shooting community when we side-step that point in favor of assuaging egos and budgets. Consistent one mile shooting does not happen through sheer power of will. Top-tier 3gunners absolutely do lean on expensive LPVOs and tricked-out rifles to maximize performance. The best guys in USPSA have frequently made some expensive modifications to their pistols and PCCs.

That said, if you’re willing to step it down to 1000-1250 yards, it’s not quite as expensive as you might imagine, and it’ll still present a real challenge.

Bang Steel in Virginia. You can get a day class for around $300. Don’t need overpriced gun/scope combo either.

I recently wrote a research paper on the most long-range weapons, and I wish I had seen your article earlier. I think that your work could help me in my research. Next time I will check your site before doing my homework.

Comments are closed.