The shot looks great in the video.

A trio of Mountain Reedbuck rush up a steep hillside; the border of South Africa and Lesotho.

A man drops, oddly crouched with a rifle on the opposite side of the canyon.

“Last one, last one!,” a rushed whisper from the PH.

“I need a distance,” from the man with the rifle.

“200, 220, 230,” from the PH.

Just 10 seconds had passed from the moment they saw the animal. The females are already out of sight, the lone male soon to follow.

A shot.

The reedbuck tumbles down the hillside and rests, still, white belly up.

The PH smiles with joy. Congratulations. Hand-shaking. They both stand up.

The camera turns off.

Then everything turns to shit.

While Jacques, my PH with Ndloti Safaris, and I are celebrating, Ron, the owner of Tactical Fitness and my hunting companion on this trip, puts down the camera and stares in the distance.

He’s the first to see the reedbuck get up and run.

The reedbuck was more than 500 yards away by the time I got back into the glass. We all saw the same thing.

The massive red gaping wound was obvious. A strike from the 28 Nosler cartridge created an exit wound so large we could actually see the bones of the shoulder articulate as the animal ran.

And run it did. Impossibly fast, impossibly far, right over a hill and out of sight.

No more smiles of joy. No more congratulations. Hand-shaking turned to hand-wringing.

We had just lost the last animal of our safari.

Mistakes were made. The first one started before the shot even occurred.

The distance call didn’t account for the high angle. I didn’t change my holds for the 6,500ft higher elevation than my original zero, and I didn’t know the round I was shooting for this one shot was moving 100 FPS faster than I had programmed for.

That series of beginner’s mistakes from a seasoned hunter meant that a shot that would have been a bit high was now 4” higher than that.

The bullet struck the baseball-sized no-man’s land between the top of the lungs and the bottom of the spine. The temporary cavitation had knocked the animal down, but clearly not out.

The next mistake was the biggest.

It’s not dead until it’s dead. I should have stayed in the glass and watched it lay there in case I needed to put another round in it.

Given the size of the property and our position on the other side of the canyon, it took some time to drive over to the last place we had seen the reedbuck. Once there, and with less than an hour of daylight left on my last full day in the country, we realized the animal could have gone a number of directions without us seeing it, including through a portion of the property that would likely fence in the cattle, but would do little to nothing to hold in our quarry.

If he went that way, he was likely in Lesotho, and gone. If he went any other way, he was fenced in. Fenced into a single high fence pen spanning thousands of acres.

Jacques came up with a plan. We’d take the half hour to drive back to the lodge, get a quick dinner, and return to hunt the night with thermal optics.

If you’ve never been on the southern African plains at night, it’s a treat. The diversity and sheer amount of wildlife moving at night is unparalleled.

But not this night.

The south wind blew hard, dropping the temperatures and blasting anything unprotected with gusts near 30mph.

Everything was hunkered down for the night, and nothing but the wind was moving.

The weather forecasts gave us much of the same throughout the night, so we decided to get a few hours sleep and get back at it in the daylight.

It was 6 hours from the moment we woke up until the time I had to be on a plane back home.

But now, at least we had the right direction.

A couple of years ago, I taught Ron my method of tracking. Whereas I forgot my own teachings, Ron didn’t. He went back to where we saw the animal last, got down on his hands and knees, and found one single drop of blood among the stone and grass.

That single drop of blood gave us the reedbuck’s direction, and told us he was almost certainly still in the Free State of South Africa.

We all spent the next 4 hours walking up and down the hills in that direction. With the wound we saw, he was very likely dead, his small and well camouflaged body tucked into the bushes.

With five men now looking, we covered a lot of ground, but to no avail. Half an hour is all we had left.

My shame at losing the animal did nothing to strengthen my hope, but Jacques’ doggedness and his supreme confidence that we would find the animal lifted my spirits.

I was checking for a dead reedbuck behind some bushes when Jacques stopped walking and brought the binoculars to his eyes. Turning to me, wide eyed, he said, “It’s him.”

And it was. From 150 yards away, the red wound on his shoulder was a beacon, if, yet again, a quickly fleeing beacon.

Jacques dropped to the ground and I dropped beside him, using his leg for support.

The reedbuck was running downward this time, back into a different portion of the same canyon as before.

“Now Jon. There’s no time!” from Jacques.

A shot.

The reedbuck tumbles down the hillside and rests. This time upside down, caught by the base of a small tree.

I chamber another round, and watch.

The animal that was impossibly alive is now, to my mind, just as impossibly dead.

Yon, our young Zulu tracker sprinted up the canyon wall, hoisted the prey on his shoulders, and was back up by our side even before we could get the rig over.

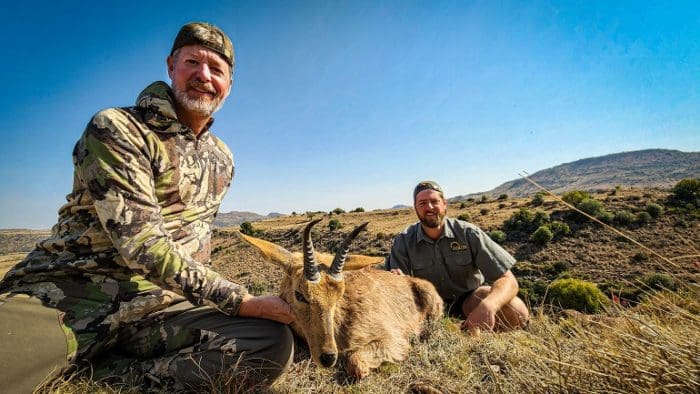

We all admired the animal with awe. He had run a full 3 miles from the point of impact to this spot, with a massive chunk taken from his shoulder. I put a bit of sweet forb in his mouth and said a prayer of thanks.

Many large, beautiful, and expensive animals would fall during that safari, but none made me doubt, or smile, like that Mountain Reedbuck.

the way lesotho is isolated is fascinating. i’ve always wanted to go there.

Lethoto is landlocked, but not isolated. From the outside looking in (literally), there’s not much worth visiting.

“…the only independent state in the world that lies entirely above 1,000 metres (3,281 ft) in elevation. Its lowest point of 1,400 metres (4,593 ft) is thus the highest lowest point of any country in the world.”

as in easily defensible isolated.

See those hills in the background behind the truck? That’s Lesotho.

I have friends there and they would disagree with you.

In this way the local populations of animals are kept in check. Both inside the United States and abroad. And their local economies are kept thriving. It is Hunter dollars that allow this to happen. And there’s nothing wrong with having a good time while you’re doing it!! Congratulations sir on a successful hunt!!

Hunter tourism is an important part of the Outdoor World economy. Capitalism at work. An exchange of resources that is profiting both sides.

edit. sorry I forgot the beginning portion.

The only way to protect and preserve wildlife is to periodically cull heard. And if it takes people travel to different parts of the United States to hunt. Or having people travel to different parts of the world to hunt. Hunting must be done.

What a elfin lame brain excuse.

In Africa these animals are semi-domesticated and bred for purpose. In any case proper CULLING should only ever be carried out by experts at the job not lame brained Americans on a Jolly-Boy Holiday for poseurs. Hunting in the true wild is very carefully controlled or it’s called POACHING and for absolute sure HUNTING does NOT HAVE to be done anywhere. but maybe CULLING does.

CULLING is NOT HUNTING. Culling is the replaceing of the natural predators that would have taken out the lame, and the sick and genetic misfits thus preserving the gene-line of healthy beasts and preventing over population.

I suggest you do a bit of research on the effects of RE-INTRODUING WOLF PACKS into YELLOWSTONE

Normally I’d gin up some fake Brit slang and/or banter in response to our resident fake-Brit boob but this is so excruciatingly bad and self-parodying it would be a complete waste of time – bravo Al, bravo, your ineptitude has left me speechless.

yeah, no. the predation does all the necessary culling.

It’s also tons of fun.

I’m glad you had a great time. Who gets the meat?

Chris in KY, in this particular case, a local old folks home.

Good article. I’ve seen some animals take some serious damage and keep on kicking. I try to always keep those experiences in mind when I’m hunting or putting an animal down (farm). Ive seen a few people try to use a .22 on animals they should’ve used something bigger on.

Craziest one personally was probably the last gator I killed. Shot it in the head, taped up the mouth then stabbed and scrambled it’s brain to be sure, but, I swear, that thing still seemed to be alive in the boat for quite some time. Eyes looking around. Probably just nerves as I made sure to cut out the brain but still, it was eerie and seemed alive somehow.

A single small spot of blood from a wound like that? Hardly Then the bloody idiot is trying to tell us that any animal with that kind of wound can still run all day and is hard to track, What an idiot. Then he tells us he cannot tell the difference between 200 and 500 yards ? The idiot c should not beallowe anywhere near the Hunting Field . Probably isn’t and that’s why he has to go to Africa. To Africa to shoot an animal ? Really?? And so elfin PROUD of it? The LAST thing I’d be proud of is shooting an animal from the wrong distance blowing it practically in half, can see the shoulder blades and spine from 500myards ? and still run miles, and then cannot track it because it did not bleed enough!! I smell a bloodybgreatb rat here .

Now you know how we feel about all your stories.

I’ve seen regular old deer do the same he’s mentioned in the article. The only bullshit around here is your posts.

See me earlier comment. This goofball has taken all the fun out of ridiculing him by being better at doing it to himself than anyone else ever was…

When you going to have a lion killing story?

Most of them animals your shooting can be found on a Texas ranch. I’d just pay some guy in texas and skip the African.

Let’s put a shaggy wig on a possum and charge folks for a lion hunt.

Well..if it was just about the killing you might be right. But even then, it’s more expensive to hunt these animals in my home state of Texas than it is to travel around the world and hunt them in their natural habitat.

“it’s more expensive to hunt these animals in my home state of Texas than it is to travel around the world and hunt them in their natural habitat.”

What!!! How is that possible???

Capiltavania, man. Capitilvania.

Supply and demand.

For instance, you can fly to South Africa, stay for a week, and take a zebra, wildebeest, and blessbok for just the price of a zebra alone here in Texas.

Stupid question maybe, how did/do you figure an animals directions from a small drop of blood loke that?

Awesome article btw.

Forp,

I don’t know the specifics for this hunt. I will share general principles.

When a hunter shoots an animal and the animal takes off running, the hunter and/or guide watches the animal until they cannot see it any more. Usually the animal runs in a more-or-less straight direction and that is where the hunter begins tracking–with the initial assumption that the animal continued running in that direction past where the hunter/guide last saw the animal.

Of course the animal could change direction at any time. So, the hunter continues to look for blood in that original straight-line direction until he/she can no longer find any blood. Once that happens, he/she goes back to the last visible blood and then fans out to look for blood in a new direction.

For example suppose that the animal started running due north and then disappeared over a hill. You start tracking it over the hill and continue to find blood drops for 50 yards continuing due north over that hill. And then you do not see any more blood drops. At that point you fan out and look for blood. All it takes is a single drop of blood to reveal the wounded animal’s new direction. In this example, if you find a single drop of blood to the east of the animal’s original direction, now you start looking east for more drops of blood.

In some rare instances, a single drop of blood will splatter and the splatter characteristics can also give a sense of which direction the animal was running.

That is how a single drop of blood can change your tracking direction.

Uncommon’s answer was a good one. In this case, it was both the location and the spatter that gave us the location and direction of travel.

Here’s a way to learn a lot about blood trailing. Go get a plastic bag. Fill it 2/3 water 1/3 olive oil and shake it good. Poke a pencil sized hole in it, and go for a walk with it. Now go for a jog. Now a run. Now stand still. Note the splatter pattern. Now wait an hour, and look again. Do this in rocks and grass and varied terrain. You’ll learn tons!

This story reminds us that hunting can go wrong in countless ways–many of which are actually dangerous for the hunter.

SASSA, the South African Social Security Agency, is supposed to provide a vital social safety net for millions of vulnerable South Africans through the distribution of social grants.

Comments are closed.