According to their website, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is “the world’s oldest and largest global environmental organisation, with almost 1,300 government and NGO Members and more than 15,000 volunteer experts in 185 countries. Our work is supported by almost 1,000 staff in 45 offices and hundreds of partners in public, NGO and private sectors around the world.” [Click here for an intro video.] You may – or may not – be surprised to learn that the IUCN’s international eco-warriors support trophy hunting. In fact . . .

An IUCN briefing published this month discusses in great detail how legal, well-regulated trophy hunting can and does generate critically needed incentives and revenue in order for government, private and community landowners to maintain and restore wildlife as a land use and to carry out conservation actions, including much-needed anti-poaching interventions.

That’s the Dallas Safari Club’s take [via ammoland.com] on the IUCN’s briefing paper Informing decisions on trophy hunting. It was prepared in the wake of the “Cecil the lion” debacle and subsequent calls for the European Union to ban the importation of hunting trophies. The IUCN acknowledges problems with the practice, but provides a compelling case for trophy hunting, worldwide.

Trophy hunting is hunting of animals with specific desired characteristics (such as large antlers), and overlaps with widely practiced hunting for meat. It is clear that there have been, and continue to be, cases of poorly conducted and poorly regulated hunting both beyond and within the European Union.

While “Cecil the Lion” is perhaps the most highly publicised controversial case, there are examples of weak governance, corruption, lack of transparency, excessive quotas, illegal hunting, poor monitoring and other problems in a number of countries. This poor practice requires urgent action and reform.

However, legal, well-regulated trophy hunting programmes can – and do – play an important role in delivering benefits for both wildlife conservation and for the livelihoods and wellbeing of indigenous and local communities living with wildlife.

The Briefing Paper is well worth a read. The most persuasive part: case studies of trophy hunting’s success in restoring populations of endangered animals. Here’s one on rhinos in South Africa and Namibia.

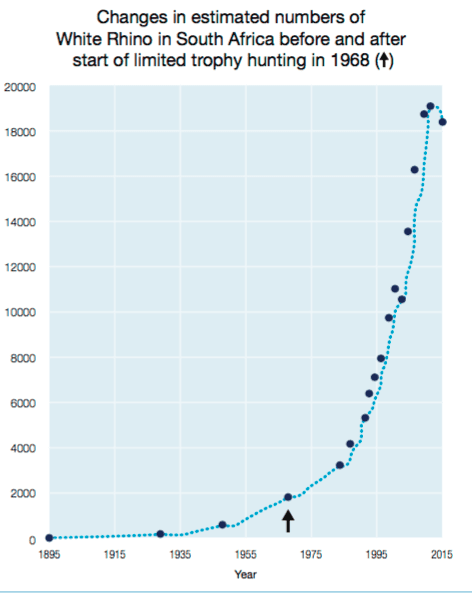

Since trophy hunting programmes were introduced for these species, White Rhino increased in South Africa from 1,800 (in 1968) to around 18,400; and Black Rhino increased in South Africa and Namibia from around 2,520 (in 2004) to around 3,500 (see Figure 1). By end 2015, these two countries conserved 90% of Africa’s rhinos, yet only 0.34% and 0.05% of their white and black rhino populations were hunted.

Not only has rhino hunting clearly been sustainable, it has played an integral part in the recovery of these species through providing incentives for private and communal landholders to maintain the species on their land, generating income for conservation and protection, and/or helping manage populations to increase population recovery.

Limited sport hunting of rhinos along with live sales and tourism has provided the economic incentives to encourage over 300 South African private land owners to collectively build their herd to ~6140 white rhinos and 630 black rhinos on 49 private/ communal land holdings – very important populations of these iconic species. This has added over 2,000 km2 of conservation land – equivalent of another Kruger National Park!

However, increasing security costs and risks due to escalating poaching and declining economic incentives have resulted in a worrying trend of private rhino owners and managers divesting

their rhino, threatening future expansion of range and numbers. Import restrictions that threaten the viability of hunting would likely further reduce incentives and exacerbate this trend.Many private reserves rely heavily on trophy hunting and that of white rhinos to cover operational expenses. For example, a South African reserve, known to the IUCN African Rhino Specialist Group, with identity concealed here for rhino security reasons, manages an increasing population of 195 white rhinos and many other species.

Their conservation efforts are self-funded. Analysis of eight years’ data revealed that only ~18% of the total reserve’s operational expenditure was generated from tourism, while trophy hunting generated the bulk of income needed to fund operational expenditure (63%). Over the last eight years, only seven (or <1% of the population annually) white rhino have been hunted on the reserve, generating US$617,000; with live sales of another 47 white rhino over the period bringing in an additional US$973,000.

The reserve allocates all of the proceeds from rhino hunting towards rhino protection and conservation management costs. Average white rhino hunting revenue in the reserve over the last eight years translated to US$400 for each living white rhino in the reserve today/year; equivalent to 29%–33% of estimated current rhino protection and law enforcement costs/ rhino/year in Kruger National Park and on Private Land of US$1,210–US$1,360/ rhino/year, respectively.

The Reserve Manager indicates that “the income from hunting in general and from the live sales of rhino, has sustained the management of the Reserve for decades” noting the recent ban on the import of lion trophies into the US has already had a negative impact on income to fund conservation with the cancellation of some hunts.

Rhino hunting has not been without its problems, with some ‘pseudo-hunters’ using the legal sport hunting route to access rhino horn for illegal sale in South East Asia. Increased regulation has seen the record high 231 rhino hunting applications in South Africa in 2011 plummet to normal levels of 62 white rhino and one black rhino hunted in 2015. In Namibia a further 3 white rhino and 1 black rhino were hunted in 2015. These numbers represent only 0.35% of the white and black rhinos conserved by these two countries, respectively, yet will have generated turnover close to US$4 million.

Just like the gun control “debate,” the fight to maintain trophy hunting is a battle between advocates using empirical data to prove effectiveness and crusaders using emotion-driven arguments without a rational basis to evoke the law of unintended consequences. In case you didn’t know.

I’d cook that right up.

I read an article that said after the Cecil circus and the decline in lion hunting, the local government was estimating they were going to have to cull around 200 lions due to overpopulation. Yeah, that’s so much better.

But if the government does it, then it’s okay. Didn’t you know that?

Jimmy Kimmel killed more lions with his big mouth than any douchebag dentist could ever dream of. Why is nobody dousing him with fake blood and chanting “MURDERER!?”

The “social justice movement is just a big frat party. When they wake up with those splitting headaches and see all the bodies that have piled up due to their bad advice they will just laugh about it over pancakes.

Right there, that’s the difference between environmentalism and conservation (ism? Not really sure what the noun form of the word is, and Google was less than helpful). Environmentalists are urban liberals who don’t actually care about the environment, just about looking eco-conscious by decrying any kind of destruction. Conservationists actually care about the environment and understand the give-and-take of ecosystems. Sometimes you have to destroy things to protect them, such as removing trees that have grown too close together to reduce the damage of a possible wildfire by creating a fire break.

Also, at this point, there’s no “man/nature” divide. We are part of every ecosystem whether we like it or not. In many cases that is going to mean active management and intervention if we want to keep things from coming off the rails.

If there were ever a species deserving of extinction, it would be American and European Urban Liberal-Progressives.

Things may get interesting in October. CITES is considering moving African lions from appendix 2 to appendix 1. Meaning they are threatened with extinction rather than let’s continue to manage them so they continue to thrive.

Yet the facts (let’s not let those pesky things get in the way) show otherwise.

Like anti-gun folks, the anti-hunting crowd rely more on feelings than facts.

would it similarly be good to protect DC live by trophy hunting in DC?

It’s nice to see the case made that local economic forces are a big factor in the success of animal population growth. The hunting business keeps many people employed and small villages with much better economies than they would have if not for the white hunters to be honest.

But the Africans have to rely on outsiders to hunt animals because it is illegal in these countries to own guns.

Now if the white liberals will just let Africans take care of their “back yard” animal issues, Africa would be much better off.

My back yard animal issues only involve deer, turkey, and the occasional coyote.

Ever consider opening your land to varmint and bird hunters then? Could bring some extra cash…

The last unicorn and a bunch of ofwg’s killed it. We can’t get a break.

I didn’t need to take any special steps when I started hunting, other than to do what Dad told me and learn as I went along.

It is a learning process for me, to try to put myself in the shoes of an adult beginner – because I simply don’t know what it’s like to be an adult beginner in hunting or shooting.

Comments are closed.